How we built Enclaves: Egress Networking

How we built our Enclaves primitive, we dig into our redesign of Enclaves egress networking with iptables.

Joe Engressia was born blind. While lacking the power of sight, his keen ear and perfect pitch kicked off phone phreaking: the proto-hacking phenomenon that was a key part of the founding story of one of the world’s biggest companies. As Steve Jobs noted, without phone phreaking, "there wouldn't have been an Apple."

Joe Engressia’s dad was a portrait photographer for school yearbooks, and the Engressias moved a lot. At four, seeking refuge from a world of tumult, he learned to work the phone like an old-timey telegraph: rapidly pressing and releasing the switch hook to simulate the pulses generated from a rotary dial phone.

Joe discovered that whistling at a pitch of fourth E above middle C, or E7 (2637 Hz), would stop any pre-recorded message. Rather than using this skill to never have to listen to a customer service ‘we appreciate your call’ hold message again, Joe called up the phone company and explained to them what had happened. The phone company thanked him for his bug report by cutting off his family’s phone access.

When we think of hacking, we immediately think of computers. But the technological and subcultural origins of hacking are closely linked with telephony. Phone phreaks were the first hackers, they just happened to use the technology of the time: the telephone. They played around with the system, exploring its nooks and crannies, and exploiting loopholes — just as hackers do today.

Although there were some nefarious phone phreaks, they were enthusiasts in the main. As Phil Lapsley, author of Exploding the Phone, notes:

“These were not people who were out to make free phone calls, you know, for the sake of making free phone calls. They were just like, ‘Wow, what happens if. What happens if I dial this number? What happens if I play this tone?’ They were simply curious.”

When AT&T implemented fully automatic telephone switches, they built it such that its entire long-distance switching system ran on twelve electronic combinations of six master tones. Frequencies at specific tones were signals to the system that a certain action had been performed. For example, a tone at 2600 Hz was an instruction to the telephone switch that the call had ended. Although simplistic systems have their merits, they have their obvious flaws too. This multi-billion dollar decision was taken down by a blind seven-year-old and his whistling.

Joe’s forays may have simply been a whistle in the dark, were it not for the wrath of the phone companies. While they had cut off his phone access as a child, the phone company threatened legal action against him as a student. Its unintended effect was that Joe was soon inundated by fellow phone phreaks across the country. What had been a speckled smattering of individuals became a movement, and Joe was their messiah.

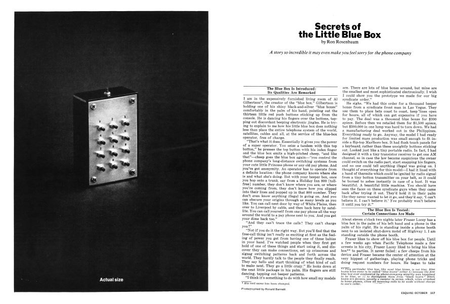

The phone phreaks also stumbled across a sacred text. Bell Labs had innocuously allowed a technical journal to publish the specific frequencies used to create these tones. While the phone companies later scrambled to withdraw the publication, the phone phreaks had copied them — even translating them into Braille for the growing number of blind phreaks.

While phone phreaking was done for many different reasons, one of the more common uses was for free long-distance calls. The telephone system worked off a tandem. Each tandem was a line with some relays that could signal another tandem on the continent. Now, usually, these tandems were direct lines. But, if there was heavy traffic on the direct tandem, you’d take a slightly circuitous route. For example, if you wanted to call from New York to San Francisco, and there’s heavy traffic; the service was programmed to send you on the next best route: perhaps from New York to New Orleans, to LA, and eventually to San Francisco. These tandems spoke to each other through tones. If you could simulate a 2600 Hz tone, this would leave an open line, allowing the caller to exploit this vulnerability for free long-distance calls.

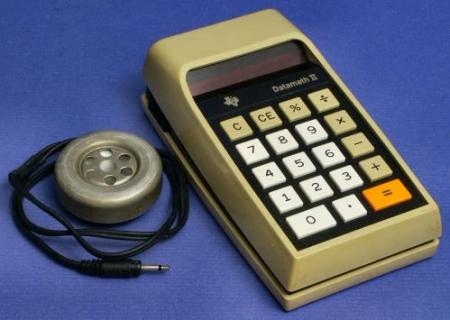

But how to simulate these tones? Not everyone could rely on having perfect pitch, so the phreaks cobbled together some rudimentary technologies. Initially, these were electric organs, cassette recorders, and doorbells; but later developed into ‘blue boxes’. The blue boxes were electronic devices that generate tones.

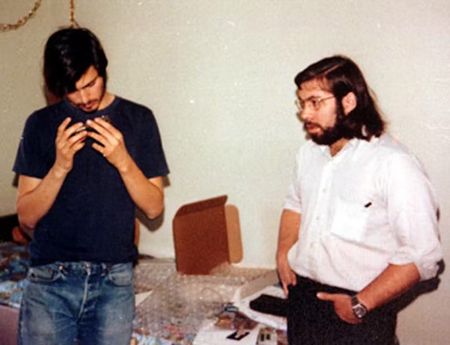

The transition to these devices did formalize the illicit nature of what could have been construed as an innocent hobby. The phone phreaks disguised their blue boxes, often as AM radios or musical equipment, and obscured their own identities in phone phreak monikers. Joe became Joybubbles, and another early phone phreaker was Captain Crunch. So-called due to his discovery that promotional toy whistles given out in the cereal of the same name generated a perfect 2600 Hz tone. There were hundreds of other phone phreaks, but the two most noteworthy might be Oaf Tober and Berkeley Blue. But you might know them better as Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, the founders of Apple.

While the two Steves were already friends, a 1971 Esquire article on phone phreaking was a key touchstone in the development of their business relationship.

"It was the most amazing article I'd ever read!" — Steve Wozniak

Woz happened across the article on his kitchen table, and was struck by a sense of kinship with the phone phreaks:

"I could tell that the characters being described were really tech people, much like me, people who liked to design things just to see what was possible, and for no other reason, really."

He devoured the piece and called Jobs. Within an hour, they’d snuck into a library at Stanford and struck gold: a reference booking listing the phone frequencies. After a quick stop off at a local electronics store, they worked through the night to try and build their own analog blue box. They got close, but were constrained by the technology: analog circuits weren’t precise enough.

Still though, Woz was hooked. This was the night before he started at Berkeley, but he found his thoughts drifting back to the blue box. Woz had been designing electrical circuits for a couple of years and thought that a digital blue box was doable.

He cracked the design by early 1972. Delighted with the digital build, as well as some clever circuitry to preserve power consumption, Woz later gushed: “I swear to this day, I have never designed a circuit I was prouder of.” High praise from the guy who would go on to design the Apple I and Apple II personal computers.

While the phone phreaks were always quite interconnected, a coincidental crossover really helped cement the phone phreak cinematic universe. Through a friend from high school, the newly christened phreaks managed to track down Captain Crunch. As Woz recalls:

“Captain Crunch comes to our door, sloppy-looking, with his hair kind of hanging down on one side. And he smelled like he hadn't taken a shower in two weeks, which turned out to be true. He was also missing a bunch of teeth."

Woz tentatively asked the traveller if he was indeed the fabled Captain Crunch.

"I am he."

Despite a close encounter with the police, the entrepreneurial Jobs spotted an opportunity. They’d managed to impress the Captain with their blue box, and it was easy enough for Woz to build; why not build more and sell them?

Innovation in tech is often centered on the technology itself, but innovative distribution is often overlooked. In the Paul Grahamian do things that don’t scale philosophy, it’s hard to think of a better example than their early door-to-door sales process. The two Steves would knock on random dorm rooms in Berkeley, asking for a made-up person. When the confused co-ed would ask “who?”, they’d respond with, "You know, the guy who makes all the free phone calls?" and make the sale.

In an attention-to-detail approach that would later define Apple’s customer obsession, Woz included a handwritten guarantee in each box. As the Steves sold up to a hundred of these blue boxes, a few fell into the hands of the FBI. The FBI lab technicians could tie together that all these blue boxes came from the same source but, fortunately, never could catch the culprits.

Totally unaware of how close they’d come to being caught, Woz was often conducting prank calls— he even called the Vatican pretending to be Henry Kissinger. A great feat, although bested by Captain Crunch, who ended up getting through to then-president Nixon.

While digitalization of the phone network ended the tone-based system, the legacy of the phreaks lives on. Most notably, according to a recent Defcon talk, phreaking still exists today in elevator phones. And, while the phreakable surface has shrunk: *“Stairwell phones, emergency phones at swimming pools, call boxes on college campuses, and other push-to-call phones in random buildings across the country are similarly exposed.” *

What had started as a smattering of socially-awkard teenagers became a movement that foiled the multi-billion dollar telecoms industry; and set the stage for the development of hacking, both white-hat and black. It also got a generation interested in technology, and subverting it. As Steve Jobs later told his biographer, without phone phreaking, "there wouldn't have been an Apple."